Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasms

Authors

INTRODUCTION

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasm (VIN) is a histologic diagnosis of a proliferative disorder of the external female genitalia. It also has been referred to as Bowen’s disease, erythroplasia of Queyrat, and carcinoma simplex.1, 2 The International Society for the Study of Vulvar Diseases (ISSVD) has established a standardized nomenclature that should be used preferentially (Table 1).3, 4, 5 Severe VIN, termed VIN III, is synonymous with carcinoma in situ (CIS) and may be referred to by either term because both are used interchangeably in the literature.6

Table 1. ISSVD standardized nomenclature for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasm

Terminology | Equivalent terms |

VIN I | Mild dysplasia |

VIN II | Moderate dysplasia |

VIN III | Severe dysplasia; carcinoma in situ; Bowen’s papillomatosis |

Specific diagnoses | |

Lichen sclerosus | |

Squamous hyperplasia | |

Paget’s disease |

ISSVD, International Society for the Study of Vulvar Diseases

Because the diagnosis and definition of VIN are currently based on light microscopy, patients with this disease undoubtedly contain a heterogeneous mixture of entities with differing clinical significance.7 Until objective molecular data are available to sort out these subgroups, it will be impossible to identify these differences by light microscopy alone, limiting clinicians to the histologic definitions in use today.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There have been no recent readily available population-based studies on the different degrees of VIN. Most of the available information in the literature is based on retrospective hospital-based studies with inherent selection biases. The true incidence of the different degrees of VIN is not definitively known. Several estimates of prevalence are available from referred patient samples. Based on small referral populations, these estimates may not be indicative of the overall VIN patient population. They may be applicable, however, to an individual clinician’s office- or hospital-based practice. Information on vulvar CIS is more complete and may be helpful in discerning the epidemiology of VIN.

In vulvar CIS, a large population-based study revealed a possible twofold increase between the early 1970s and the late 1980s.8 The cause of this increasing incidence may be related to an increasing exposure to the reported causative agent, human papillomavirus (HPV).1, 2 A heightened awareness of HPV alternatively may be the cause of this apparent rise in incidence. Although no definitive conclusions can be made regarding the cause of this possible increase in CIS, similar trends may be anticipated in the less severe forms of VIN. This study did not detect a similar increase in the rate of invasive vulvar cancer, reinforcing that the link between VIN and cancer is not absolute.9 Several epidemiologic studies from Europe reported an increased incidence of VIN, with younger women showing the greatest rise. Iversen and Tretli,10 using the Cancer Registry of Norway, showed a threefold increase in incidence rate of VIN from 1973 through 1977 to 1988 through 1992. Over the same time intervals, the age-adjusted incidence rate for invasive vulva cancer did not change significantly.10 In another retrospective analysis of the periods 1985 through 1988 and 1994 through 1997, Joura and colleagues11 reported a tripling of incidence of women with high-grade VIN. Although the incidence of vulvar carcinoma also remained stable, the subset of women less than 50 years old showed an increased incidence of invasive vulvar cancer by 157%.11 A similar subset emerged from a cohort study of the periods 1965 through 1974 and 1990 through 1995 of women younger than 50 years old with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva.12

Based on data from nine Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Cancer Registries, certain demographic observations have been made about women diagnosed with vulvar CIS. In a 10-year period, the greatest increase in incidence of VIN was seen in white women less than 35 years old, for whom the rate of vulvar CIS nearly tripled to 0.8/100,000 women-years. Despite this rise, black women had higher rates of severe VIN than white women in every age category throughout the 10-year period. The peak incidence of VIN III was found among black women, 35–54 years old, from 1985 to 1987, when the rate reached 5.6/100,000 women-years.8 The rate rose in all ages and both races throughout the time periods studied. The age group with the highest incidence changed, however, from women older than age 55 in the 1970s to women aged 35–54 during 1985–1987. A possible confounder in this study is that it occurred during the time of changing VIN definitions.3 Changes in definition often affect disease surveillance data and may have influenced these results. Earlier investigators identified similar patterns in patient characteristics.13 Patient characteristics do not completely explain disease rates because there is also an interaction with the geographic location of the patient and disease prevalence.14

Demographic variables possibly responsible for the observed earlier peak ages include changes in sexual behavior and tobacco use. As with other neoplasms, tobacco use, especially current use, is associated with an increased risk of VIN III.15 A similar relationship has been described for increasing numbers of sexual partners.16 Epidemiologic studies, especially in cervical neoplasms, suggest a sexually transmitted pattern of HPV infections.17 Non-sexually transmitted HPV infection also has been suggested.18, 19, 20, 21 VIN-associated HPV is found in younger patients and is correlated with sexual history, including number of partners and age at first intercourse.22, 23 It is not surprising, given these similar risk factors, that an association between VIN and cervical dysplasia has also been observed, with approximately 15% of VIN patients having a concurrent cervical neoplasia.1, 2, 24

The association between lesser degrees of VIN and vulvar carcinoma is not well defined.25 However, weak epidemiologic data and extrapolation from cervical HPV disease suggest a causal association. Most patients with VIN generally are reported to be on average 10–20 years younger than patients with invasive vulvar cancer.2 Approximately 9–22% of patients referred for treatment of VIN are found to have invasive cancer on closer examination.26, 27, 28 Jones and McLean29 reported five patients with VIN III who were followed for 2–8 years; all developed invasive cancer. In comparison, there are more than five cases, reported by several authors, of VIN spontaneously regressing.24, 30 Finally, molecular DNA analysis has been interpreted as confirming the malignant potential of VIN lesions but only in a few cases.31, 32 Investigations have confirmed that VIN is a heterogeneous disease, characterized by a variable malignant potential.33 This heterogeneity may be the reason for the weak and inconsistent relationship observed between VIN and vulvar cancer in epidemiologic studies. VIN and vulvar cancer share many characteristics. Although the causal relationship is highly suspected, it remains unproven, and the natural history of VIN is unclear. To date, there is no specific information on the role that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) plays in VIN. Theoretically, HIV infection could be a risk factor for the development of VIN. There are only preliminary reports on HIV-positive women and vulvar lesions.34 Increased incidence of condyloma, VIN, and vulvar cancer has been reported in women infected with HIV.35 The prevalence of vulvar condyloma and VIN among HIV-seropositive women ranges from 5.6 to 16%.36, 37, 38 Management of VIN in HIV-positive women may be extrapolated from the experiences with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in similar populations. Until more data become available, HIV-infected women with VIN may benefit from vigilant colposcopic evaluation and biopsies of the vulva.35

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia is more prevalent in HIV infected women than uninfected. A prospective study of 925 women found a higher incidence in HIV-positive women than HIV-negative controls over a median follow-up of 3.2 years.39 Seven per cent developed high grade intraepithelial lesions during this period. This underscores the importance of a thorough inspection of the vulva in HIV-positive women, with colposcopic and histologic evaluation of any abnormality.

CAUSE

It is likely that there are multiple causes of VIN, given the heterogeneity of this disease. Of these causes, it seems that certain serotypes of HPV have a significant role as the cause of a large proportion of VIN lesions.9 This may be especially true in younger patients.40 HPV types 6, 11, 16, and many others have been identified in VIN biopsy material. Certain types are found more often than others. Approximately 80% of VIN lesions have HPV-16 detectable by polymerase chain reaction.41 In a case-control seroepidemiologic study, women with HPV-16 antibodies had a 5.3- to 20-times increased risk for vulvar neoplasia.42 Other significant risk factors include the number of lifetime sexual partners and genital herpes simplex virus infection.

Evidence for a causative role is mounting. HPV may induce neoplastic lesions by altering gene expression with subsequent abnormal cellular protein production. L2 and E7 messenger RNA is found at increasing frequency as the degree of VIN lesions worsens.43 HPV oncoproteins E6 and E7 can inactivate tumor-suppressor genes RB and p53, although the interaction is not essential for eukaryotic immortalization.44 These observations provide the strongest evidence of a causative role for HPV in at least some cases of VIN.

Other possible causes of VIN and vulvar cancer are under investigation. Tate and associates45 reported evidence supporting a monoclonal cause of VIN. This cause is of particular relevance in cases of VIN without HPV infection. The gene that codes for proteins pRB2/p130 and p27kip1 has been studied as a possible tumor-suppressor gene. Data suggest that a loss of protein products expression from this gene is associated with increased risk of vulvar carcinoma.46 Lee and associates47 investigated the role of p53 mutation in HPV-negative vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. An alteration in p53 activity, in the absence of HPV involvement, seems to contribute to development of carcinoma of the vulva.47

HISTOLOGY

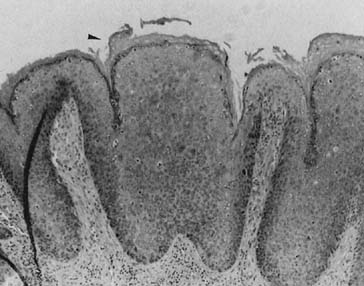

The histologic classification of VIN is similar to that of cervical intraepithelial neoplasms.27 Lesions are characterized by nuclear atypia and an increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. There is also a loss of maturation normally seen as the basal cells migrate toward the surface epithelium. When these features involve the lower third of the epidermis, it is referred to as VIN I. Involvement of the middle third is designated VIN II, and complete involvement is designated VIN III (Fig. 1).

|

The average depth of neoplastic involvement is approximately 0.38 mm. Involvement of sebaceous glands or hair follicles occurs in approximately 30% of cases. When they are involved, the depth of VIN may extend to 0.77 mm. The total histologic involvement rarely extends for more than 1 mm in the nonhairy skin or greater than 2 mm in the hairy skin areas.48 These histologic measurements form the basis of current ablative therapies.

VIN lesions are subdivided into three types based on their morphologic and histologic features:

As is common with histopathologic diagnoses, the degree of agreement between pathologists varies significantly. The agreement rate can be 5% for VIN I and no better than 70% for VIN II or III.49 It may be advisable for the clinician when treating a patient with a diagnosis of VIN to review the histology slides personally before making any major therapeutic decisions. Additional studies, including MIB-1 (proliferation-associated nuclear antigen to Ki67) staining or other molecular markers, may aid in differentiating the degree of VIN among pathologists. The interobserver variation with sole use of MIB-1 is better than with the use of hematoxylin and eosin stains in VIN. There was no improvement by the combined use of hematoxylin and eosin and MIB-1-stained slides. The use of MIB-1 in grading VIN reduces confusion between VIN II and VIN III by fourfold.50 A two-tailed grading system for VIN seems to already work in daily practice.

DIAGNOSIS

There is no single characteristic or pathognomonic feature that can facilitate the diagnosis of VIN. A biopsy should be performed on any new vulvar lesion because this can be accomplished easily with little morbidity using a local disinfectant and lidocaine. Elevated, white irregular lesions may be considered at highest risk for VIN. In one series, 90% of patients exhibited this characteristic.51 These lesions can occur on any location of the vulva but have been described most frequently on the right lower border of the labium majora and minora at the 8 o’clock position.52

As with the other aspects of this disease, the symptoms of VIN are variable. Pruritus is a common complaint, affecting approximately 60% of patients, although 48% may be asymptomatic.51, 53 Other investigators reported a lower asymptomatic rate of approximately 20%.54 Approximately 17% of patients present with complaints of a mass.52 Given the protean manifestations of VIN, the clinician must examine the perineum thoroughly, including the vulva and rectum, at every routine annual examination.

A thorough pelvic inspection must be performed of the vulva for any color change, masses, or ulceration. Most VIN lesions are located in the non-hairy portion of the vulva and tend to be multifocal.55 Although these lesions are often raised and may vary in color from white to red, pink, gray, or brown, there is no pathognomonic clinical appearance. Varying appearances may be seen in the same patient. This underscores the importance of biopsy of any lesion that does not respond to conservative treatment.

When the diagnosis of VIN has been made, magnification of the vulva using a colposcope may improve the sensitivity of detecting adjacent lesions. Lower powers may be utilized than those used for colposcopy. Vulvoscopy is done after application of 5% acetic acid to the vulva for several minutes. Intraepithelial neoplasia produce well-demarcated aceto-white lesions that may have punctations. Vascular abnormalities may indicate invasive cancer. Some clinicians will then paint the vulva with 1% toluidine blue which is then washed off with acetic acid after 2 minutes. Any abnormal area that retains blue dye should be biopsied.

The importance of vulvoscopy is based on the observed prevalence of microscopic abnormalities adjacent to the gross lesion. In some series, additional areas of VIN have been found in 80% of the areas adjacent to the primary lesion.52 This high rate of concurrent disease is most characteristic of younger women. Women older than age 40 have a lower, although still significant (35%), incidence of VIN adjacent to the primary lesion.52 Not even invasive cancer is always associated with adjacent VIN lesions. Of vulvar cancer cases, 40% may not show any epithelial abnormalities in the adjacent tissue.56 It is always important to examine the entire area at risk, especially in younger patients, and to consider using colposcopic magnification. If acetic acid fails to show any other abnormal areas in a patient at high risk for multifocal disease, one may consider toluene blue application. Dye-stained areas may represent other VIN areas.57

There is no direct comparison in a well-designed trial to compare acetic acid with toluene blue. Acetic acid has become the current standard. Additional diagnostic modalities may include 5-aminolevulinic acid with wavelength-specific detection devices.

VIN can appear at any time and under any circumstances. This makes diagnosing VIN, delineating its extent, and excluding cancer potentially difficult. Even with thorough, long-term surveillance, it is impossible for these objectives always to be achieved.

TREATMENT

Treatment is justified largely for the prevention of progression to invasive cancer and for the relief of symptoms while preserving the normal anatomy and function. Management options include wide local excision, skinning vulvectomy, laser ablation, and topical treatments. Because of the superficial nature of VIN, deep resections are not necessary. There are no randomized trials comparing different modalities. Case reports demonstrate similar efficacy.58 There is, however, a diagnostic advantage with excision over ablative and topical treatments when an unsuspected invasive carcinoma is present.

Wide local excision: Local excision may be performed for small individual lesions of 1–2 cm in size, making sure to leave a 1 cm margin with primary reapproximation of the edges.

Skinning vulvectomy: For the patient who has more extensive disease, multifocal or confluent, a skinning vulvectomy may be performed. The vulvar skin is removed, preserving the subcutaneous tissue. Primary reapproximation or a split thickness skin graft may be performed for closure.

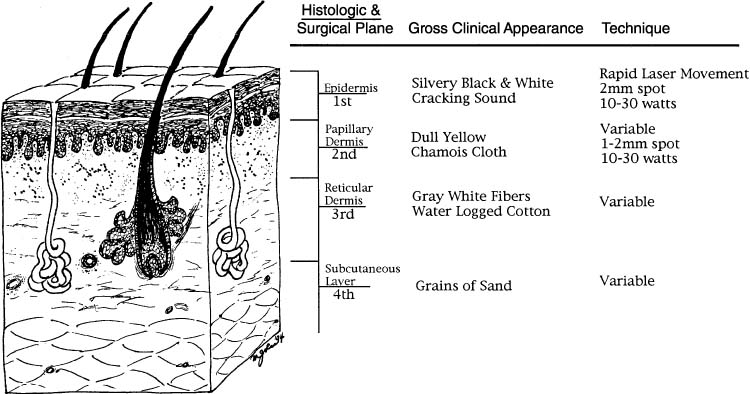

Laser ablation: Laser therapy is currently the most popular method of treatment and may be especially valuable for women with multifocal or extensive disease. This modality is most effective for women with VIN I and II disease.59, 60 However, because tissue is not excised, the coexistence of invasive cancer must be excluded by the liberal use of colposcopic directed biopsy prior to therapy. Prior to treatment, the area is defined and outlined using colposcopy after the application of 5% acetic acid. This is important because the leading edge of thermonecrosis produces a confusing pseudowhite appearance. During therapy, colposcopy is utilized to control the depth of destruction to 1 mm in non-hairy and 3 mm in hairy areas.61 It is imperative not to exceed these guidelines on depth of destruction to preserve the skin appendage and maximize the cosmetic advantage over excision. One third of patients treated with this modality will require repeat procedures to control their disease.

Patients more likely to progress include those with high-risk molecular markers. Patients who are at risk for progression include immunocompromised HIV-positive women and transplant recipients. Other patients may be at high risk for progression based on molecular markers, such as multifocal disease, presence of VIN III, and markers of angiogenesis. Pregnancy may represent a transient immunosuppressive condition. As such, lesions that have been adequately examined on biopsy specimens to exclude cancer may be observed for spontaneous regression. It is imperative, however, to note the difficulty in excluding cancer in any lesion short of its complete excision.62

Despite the uncertainty that surrounds the prognosis of VIN lesions and their association with cancer, at this time, it is traditional to treat all VIN lesions after a variable period of observation to establish the diagnosis, rule out invasion, and document persistence.1, 2, 27, 63 After cancer has been excluded, it may be appropriate under certain circumstances, such as the third trimester of pregnancy, to observe the patient for several months, hoping for spontaneous regression of the lesion. As previously mentioned, there are many reports in the literature of vulvar CIS spontaneously resolving.24, 30, 64 Aggressive treatment and follow-up of a large series of patients with VIN III was reported to be highly successful in preventing invasive disease. In a group of 102 patients with VIN III, treated and followed for 15 years, only one case of vulvar cancer was reported.65 In another group of 113 patients analyzed between 1961 and 1993, 87.5% of untreated patients progressed to invasive vulvar cancer, and 3.8% of treated patients were later diagnosed with invasive vulvar carcinoma.66

One of the most important parts of treatment is delineation of the boundaries of disease. Many patients with VIN have multifocal or multicentric disease.24, 27, 67Multifocal is defined as different sites on one organ and can affect 84% of patients.67 Multiple lesions on the vulva would be considered multifocal. Multicentric refers to disease on different organs at the same time, such as the vulva and the cervix. Of patients with VIN III, 35% have either the vagina or the cervix involved with a squamous cell neoplasia.68 For this reason, all patients with VIN should have a Papanicolaou smear and careful examination of the perineum, vagina, cervix, and anus.69 This approach is especially recommended for HIV-positive women, who may be at higher risk for multicentric disease.34 The clinician must consider the entire extent of the abnormalities present before initiating a treatment plan.

The most challenging VIN patients to treat are those who are immunocompromised by either transplants or HIV disease. For these patients, some sort of long-term maintenance therapy may be effective, such as weekly topical 1% 5-fluorouracil cream.70 Additional options include combination therapy with immunomodulators.71 In a small crossover study with no placebo control, VIN seemed to have responded to interferon-α.72 In addition to interferons, retinoids may be another area with significant therapeutic potential. Retinoic acid has shown efficacy in treating cervical intraepithelial lesions and has been shown to be active on vulvar dystrophies.73 Given the high spontaneous regression rate of VIN, however, these treatments are considered experimental and should be used only in investigational settings.

PROGNOSIS

The natural history of VIN varies from persistence to progression to remission.74, 75 A review of over 3000 patients with VIN III reported progression to invasive ulcer in 9% over 1–8 years. Spontaneous regression occured in 41 of 88 patients, all of whom were under the age of 35. Recurrence of disease occurs in approximately one third of patients regardless of the treatment modality, underscoring the importance of close follow-up.75 Risk factors for recurrence include high-grade disease, multifocal lesions, and positive margins on biopsy.60, 76, 77 Given these risks, it is imperative that long-term follow-up of the genital tract with close observation and colposcopic assessment is followed.

SUMMARY

VIN is a benign neoplastic lesion often associated with vulvar cancer. It should be treated when symptomatic and, possibly, to prevent the development of a malignant lesion. Only an appropriately directed biopsy can make an accurate diagnosis and exclude a concurrent cancer. Given the lack of objective comparative data, no firm recommendations can be made regarding optimal treatment, although minimally destructive techniques may be preferred.

REFERENCES

Gunter D, Lawrence WD. Vulvar dystrophy and neoplasia. In: Gusberg D, Shingleton HM, Deppe G (eds), Female Genital Cancer. p 227, New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988 |

|

Premalignant and malignant diseases of the vulva. In: Herbst AL, Mishell DR, Stenchever MA, Droegemueller W (eds), Comprehensive Gynecology. p 991, St. Louis: Mosby; 1992 |

|

Report of the ISSVD Terminology Committee. Proceedings of the VIII World Congress J Reprod Med 1986;31:975 |

|

New nomenclature for vulvar disease. Report of the committee on terminology of the International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease. J Reprod Med 1990;35:483 |

|

Wilkinson EJ. The 1989 Presidential Address. The International Society for the Study of Vulvar Disease J Reprod Med 1990;35:981 |

|

Campion MJ, Singer A. Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia: Clinical review. Genitourin Med 1987;63:147 |

|

Parks JS, Jones RW, McLean MR et al. Possible etiologic heterogeneity of VIN: A correlation of pathologic characteristics with HPV detected by in situ hybridization and PCR. Cancer 1991;67:1599 |

|

Sturgeon SR, Brinton LA, Devesa SS, Kurman RJ: In situ and invasive vulvar cancer incidence trends (1973–1987). Am J Obstet Gynecol 166:1482, 1992 |

|

Van Beurden M, Ten Kate FJW, Smits HL et al. Multifocal vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade III and multicentric lower genital tract neoplasias associated with transcriptionally active human papillomavirus. Cancer 1995;75:2879 |

|

Iversen T, Tretli S: Intraepithelial and invasive squamous cell neoplasia of the vulva: Trends in incidence, recurrence, and survival rate in Norway. Obstet Gynecol 91:969, 1998 |

|

Joura EA, Losch A, Haider-Angeler M, et al: Trends in vulvar neoplasia: Increasing incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamouscell carcinoma of the vulva in young women. J Reprod Med 45:613, 2000 |

|

Jones RW, Baranyai J, Stables S: Trends in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: The influence of vulvar intraepithelialneoplasia. Obstet Gynecol 90:448, 1997 |

|

Franklin EW, Ruffedge FD: Epidemiology of epidermoid carcinoma of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 39:165, 1972 |

|

Frisch M, Goodman MT: Human papillomavirus–associated carcinomas in Hawaii and the mainland U.S. Cancer 88:1464, 2000 |

|

Dahling JR, Sherman KJ, Hislop TG, et al: Cigarette smoking and the risk of anogenital cancer. Am J Epidemiol 135:180, 1992 |

|

Brinton LA, Nasca PC, Mallin K, et al: Case-control study of cancer of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 75:859, 1990 |

|

Rylander E, Ruusuvaara L, Almstromer MW, et al: The absence of vaginal HPV 16 DNA in women who have not experienced sexualintercourse. Obstet Gynecol 83:735, 1994 |

|

Craigo J, Hopkins M, Delucia A: Uterine cervix adenocarcinoma with both human papillomavirus type 18 and tumor suppressor gene p53 mutation from a woman having an intact hymen. Gynecol Oncol 59:423, 1995 |

|

Obalek S, Misiewicz J, Jablonska S, et al: Childhood condyloma acuminatum: Association with genital and cutaneous humanpapilloma viruses. Pediatr Dermatol 10:101, 1993 |

|

Roden RB, Lowy DR, Schiller JT: Papillomavirus is resistant to desiccation. J Infect Dis 176:1076, 1997 |

|

Tay SK, Ho TH, Lim-Tan SK: Is genital human papillomavirus infection always sexually transmitted? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 30:240, 1990 |

|

Ho L, Tay SK, Chan SY, Bernard HU: Sequence of variants of HPV type 16 from couples suggest sexual transmission with low infectivity and polyclonality in genital neoplasms. J Infect Dis 168:803, 1993 |

|

Kiviat NB, Koutsky LA, Paavonen JA, et al: Prevalence of genital papilloma virus infection among women attending a college student health clinic or a STD clinic. J Infect Dis 159:293, 1989 |

|

Friedrich EG, Wuilkenson EJ, Fu YS. Carcinoma in situ of the vulva: A continuing challenge. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1980;136:839 |

|

Barbaro M, Micheletti L, Preti M et al. Biological behavior of VIN: Histologic and clinical parameters. J Reprod Med 1993;38:108 |

|

Chafe W, Richards A, Morgan L, Wilkinson E. Unrecognised invasive carcinoma in VIN. Gynecol Oncol 1988;31:154 |

|

Intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva and vagina. In: Kaufman RH, Friedrich EG, Gardner HL (eds), Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina. 3rd ed. p 159, Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1989 |

|

Modesitt SC, Waters AB, Walton L et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III: Occult cancer and the impact of margin status on recurrence. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92: 962 |

|

Jones RW, Mclean M. Carcinoma in-situ of the vulva: A review of 31 treated and 5 untreated cases. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68:499 |

|

Dean RE, Taylor ES, Weisbrod DM, Martin JW. The treatment of premalignant and malignant disease of the vulva. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1974;119:59 |

|

Fu YS, Reagan JW, Townsend DE et al. Nuclear DNA study of vulvar intraepithelial and invasive squamous neoplasms. Obstet Gynecol 1981;57:643 |

|

Dinh TV, Powell LC Jr, Hannigan EV et al. Simultaneously occurring condylomata acuminata, carcinoma in situ and verrucous carcinoma of the vulva and carcinoma in situ of the cervix in a young woman: A case report. J Reprod Med 1988;33:510 |

|

Anderson WA, Franquemont DW, Williams J et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma and papilloma virus: Two separate entities? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165:335 |

|

Del Priore G, Lee MJ, Barnes M et al. Inadequacy of standard treatment of genital lesions in HIV+ patients. Int J Gynecol Obstet 1994;47:273 |

|

Spitzer M. Lower genital tract intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-infected women: Guidelines for evaluation and management. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1999;54:131 |

|

Byrne MA, Taylor-Robinson D, Munday PE, Harris JR.The common occurrence of human papillomavirus infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women infected by HIV. AIDS 1989;3:279 |

|

Chiasson MA, Ellerbrock TV, Bush T et al. Increased prevalence of vulvovaginal condyloma and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol 1997;89:690 |

|

Chirgwin KD, Feldman J, Augenbraun M et al. Incidence of venereal warts in human immunodeficiency virus infected and uninfected women. J Infect Dies 1995;172:235 |

|

Conley LJ, Ellerbrock TV, Brush TJ et al. HIV-1 infection and risk of vulvovaginal and perianal condylomata acuminata and intraepithelial neoplasia: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2002;359:108 |

|

Schneider A, Meinhardt G, Kirchmayr A, Schneider V. Prevalence of HPV genomes in tissue from lower genital tract as detected by molecular in situ hybridization. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1991;10:1 |

|

Hording U, Daugaard S, Iversen AK et al. HPV-16 in vulvar carcinoma, VIN, and associated cervical neoplasias. Gynecol Oncol 1991;42:22 |

|

Hildesheim A, Han C, Brinton LA et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 and risk of preinvasive and invasive vulvar cancer: Results from a seroepidemiological case-control study. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:748 |

|

Auvinen E, Kujari H, Arstila P, Hukkanen V. Expression of the L2 and E7 gene in HPV type 16 in female genital dysplasias. Am J Pathol 1992;141:t217 |

|

Demers GW, Halbert CL, Galloway DA. Elevated wild type p53 levels in human epithelial cell lines immortalized by the HPV type 16 E7 gene. Virology 1994;198:169 |

|

Tate JE, Mutter GL, Boynton KA, Crum CP. Monoclonal origin of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and some vulvar hyperplasias. Am J Pathol 1997;150:315 |

|

Zamparelli A, Masciullo V, Bovicelli A et al. Expression of cell-cycle-associated proteins pRB2/p130 and p27kip1 in vulvar squamous cell carcinomas. Hum Pathol 2001;32:4 |

|

Lee YY, Wilczynski SP, Chumakov A et al. Carcinoma of the vulva: HPV and p53 mutations. Oncogene 1994;9:1655 |

|

Shatz P, Bergeron C, Wilkinson EJ et al. VIN and skin appendage involvement. Obstet Gynecol 1989;74:769 |

|

Preti M, Ronco G, Ghiringhello B, Micheletti L. Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva:Clinicopathologic determinants identifying low risk patients. Cancer 2000;88:1869 |

|

Van Beurden M, De Craen AJM, De Vet HCQ et al. The contribution of MIB 1 in the accurate grading of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Pathol 1999;52:820 |

|

Brinton LA, Nasca PC, Mallin K et al. Case-control study of cancer of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:859 |

|

Bernstein SG, Kovac BR, Townsend DE, Morrow CP. Vulvar carcinoma in situ. Obstet Gynecol 1983;61:304 |

|

Dinh TV, Powell LC Jr, Hannigan EV et al. Simultaneously occurring condylomata acuminata, carcinoma in situ and verrucous carcinoma of the vulva and carcinoma in situ of the cervix in a young woman: A case report. J Reprod Med 1988;33:510 |

|

Buscema J, Woodruff JD, Parmley TH, Genadry R. Carcinoma in situ of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol 1980;55:225 |

|

Rodolakis A, Diakomanolis E, Vlachos G et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) – diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Eur J Gynecol Oncol 2003;24:317 |

|

Borgno G, Micheletti L, Barbero M et al. Epithelial alterations adjacent to 111 vulvar carcinomas. J Reprod Med 1988;33:500 |

|

Joura EA, Zeisler H, Losch A et al. Differentiating vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia from nonneoplastic epithelial disorders: The toluidine blue test. J Reprod Med 1998;43:671 |

|

Shaft MI, Luesley DM, Byrne P et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia – management and outcome. Br J Obstet Gynecol 1989;96:1339 |

|

Buscema J, Woodruff JD, Parmley TH, Genadry R. Carcinoma in situ of the vulva: Obstet Gynecol 1980;55:225 |

|

Kuppers V, Stiller M, Somville T, Bender HG. Risk factors for recurrent VIN. Role of multifocality and grade of disease. J H Reprod Med 1997;24:140 |

|

Wright VC, Davies E. Laser surgery for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: Principles and results. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;156:274 |

|

Del Priore G, Schink JC, Lurain JR. A two step approach to the treatment of invasive cancer in pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Obstet 1992;39:335 |

|

Hacker NF, Eifel P, McGuire W, Wilkinson EF. Vulva. In: Hoskins WD, Perez CA, Young RC (eds), Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. p 536, Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1992 |

|

Jones RW, Rowan DM. Spontaneous regression of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 2–3. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:470 |

|

Brogno G, Micheletti L, Barbero M et al. Epithelial alterations adjacent to 111 vulvar carcinomas. J Reprod Med 1988;33:500 |

|

Jones RW, Rowan DM. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III: A clinical study of the outcome in 113 cases with relation to the later development of invasive vulvar carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 1994;84:741 |

|

Bernstein SG, Kovac BR, Townsend DE, Morrow CP. Vulvar carcinoma in situ. Obstet Gynecol 1983;61:304 |

|

Bronstein J, Kaufman RH, Adams E, Adler-Storthz K. Multicentric intraepithelial neoplasias involving the vulva: Clinical features and associations with HPV and HSV. Cancer 1988;62:1601 |

|

Schlaerth JB, Morrow CP, Nalick RH, Gaddis O. Anal involvement by carcinoma in situ of the perineum in women. Obstet Gynecol 1984;64:406 |

|

Shilman FH, Sedlis A, Boyce JG. A review of lower genital neoplasias and the use of 5-FU. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1985;40:190 |

|

Davis G, Wentworth J, Richard J. Self-administered topical imiquimod treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. J Reprod Med 2000;45:619 |

|

Spirtos NM, Smith LH, Teng NNH. Prospective randomized trial of topical alpha-interferon (alpha-interferon gels) for the treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III. Gynecol Oncol 1990;37:34 |

|

Markowska J, Wiese E. Dystrophy of the vulva locally treated with 13-cis retinoic acid. Neoplasma 1992;39:133 |

|

Jones RW, McLean MR. Carcinoma in situ of the vulva: a review of 31 treated and five untreated cases. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68:499 |

|

Van Seters M, Van Beurden M, De Craen AJ. Is the assumed natural history of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III based on enough evidence? A systematic review of 3322 published patients. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:645 |

|

Modesitt SC, Waters AB, Walton L, et al. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III:Occult cancer and the impact of margin status on recurrence. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:962 |

|

Hording U, Junge J, Poulsen H, Lundvall F. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia III. A viral disease of undetermined progressive potential. Gynecol Oncol 1995;56:276 |